Several

members of the Skyliners hiking group had long wanted to visit the

site of the 1938 Vultee plane crash. A 2011 article in the Verde

Independent1,

a local newspaper, had whetted our interest and we had already made

one unsuccessful attempt last February only to be foiled by an

18-inch snow cover on top of the mountain. Now, reinforced by the

accompaniment of Bill Reller, who had visited the site a number of

years ago, we set out for another attempt.

Several

members of the group left from Cottonwood and drove to Sedona where

we met with others at the Burger King Restaurant. From there we

continued north on Hwy 89A to meet the final members of our group at

Indian Gardens in Oak Creek Canyon. We then proceeded on up the

canyon toward Flagstaff, turning left onto Forest Road 535 between

mile markers 390 and 391. The best directions we had to the site

started at the East Pocket Lookout Tower and we originally planned to

start our search from there. The distance to the tower from where we

first turned onto FR 535 turned out to be 23.1 miles. The first 5.5

miles (FR 535) was well maintained, the second 3.3 miles (FR 536)

contained a few large mudholes that we had to maneuver around and the

third section (FR 231) was well maintained but with a few rough

spots. With care, the entire route could have been traversed in a

normal passenger vehicle, although a high-clearance vehicle is

recommended.

As

noted, our original intent had been to drive all the way to the

lookout tower and start our search from there. The very sketchy

directions we had used the tower as a reference point. We found out

later that it is not possible to drive all the way to the tower; the

road is blocked by a closed gate about 0.5 miles short of it.

As

it were. Bill Heller remembered turning off FR 231 for the crash site

before actually reaching the tower. That was true; however, we

turned off about 1.4 miles too soon. About 0.4 miles after turning

off, we reached a spacious parking area, located right on the rim

that, that provided an excellent view of the country below us.

|

From the lot where we parked – looking across Sedona and the

red rock country

|

This

seemed as good a place as any for a group photograph.

Although

it was now pretty obvious that we were not as near the crash site as

we had planned, we decided to leave the cars and start our hike from

here anyway.

It

was not as though the crash site were unknown; a good number of

reports are to be found describing previous visits to it. However,

nowhere in any of these reports had I found location coordinates or a

good description of how to get there. I think that is partly because

the place is so deceptively simple to find once you know where it is.

In our case, we were sure that if we just traveled along the rim

toward East Pocket, we could not fail to find it.

As

we made our way east along the rim, we were constantly treated to

great views out over the red rock country. The below photograph,

looking across Sedona to Airport Mesa, shows faint contrails from an

air show currently in progress there.

|

Contrails above airport, see slightly right and below center

|

After

traveling for about half a mile along the rim we were once again very

close to FR 231 on our left. It grew farther away as we continued

along the rim but then grew closer again until, about 1.3 miles from

the parking lot, we found ourselves actually hiking on the forest

road. We continued along it for about 0.2 miles until we came to an

old road, now closed to vehicular traffic, that I later learned was

old FR 231, that once led to East Point Tank. Looking straight ahead

on the main road (FR 231), we could see a gate across that road about

a hundred yards ahead. Someone remembered the gate from a previous

trip to the area and thought it was very near the crash site, so we

turned south on old FR 231 road and then left it after a short

distance to follow more closely along the rim.

When

we had hiked far enough that we thought we should have encountered

the crash site, we decided to turn northeast and hike to the tower.

We could eat lunch there, reorient ourselves and get a fresh start on

our search. Additionally, we had been told that the tower would be

manned and that we might be able to arrange a visit to the

observation booth. That turned out to be the case and the attendant

was quite helpful in providing us some additional information to aid

us in our search.

After

everyone had visited the tower and we had eaten lunch, we headed down

FR 231 to the gate and the junction with old FR 231 just beyond it.

It turns out that we were actually headed in the right direction when

we had previously turned south on that road. We just hadn’t gone

far enough. At the tower, we were joined by a Lady from Mesa, AZ who

had hiked up A B Young trail and who stayed with us for the remainder

of our hike before heading back the way she had come.

The

distance to the junction from the tower proved to be just 0.6 miles,

as measured by GPS, and on reaching it we once again headed south

along the rim. This time we followed the old roadbed for 0.3 miles,

to the top of a fairly steep hill, before it veered to the east and

we left it to travel south along the rim. It was a lot farther than

we had expected and we were about to turn back, thinking that we had

simply missed it among the numerous ferns growing along the rim and

now sporting their fall rust color. Fortunately, just at that moment

someone spotted the small white cross erected at the site in 2011 by

Peter Vultee, Jerry's son, and his cousin John Vultee2.

We had traveled, following closely along the rim as we did, some 1.3

miles from FR 231. Much farther than any of us had thought. The

trip back, with no longer any need to hug the rim, was a little

shorter, about 1.1 miles.

|

Memorial cross erected at the Vultee crash site

|

The

blowup displayed below shows

the plaque mounted in the center of the cross.

|

Enlarged view of plaque mounted on cross

|

The

remains of a major part of the airframe assembly can be seen to the

right of the cross in the above photograph and debris is scattered

over a relatively small area extending from there to the left of the

cross. This debris field is seen from another angle in the below

photograph.

|

Vultee crash site debris field

|

The

major part of Jerry Vultee's life and career, along with the history

of the company he founded are described in an article appearing on

the Davis-Monthan Aviation field Register web

page3

and the aforementioned article published in the Verde

Independent speculates on why

he was flying in such bad weather. I will not elaborate further

here, but will leave it to interested readers to review those sources

themselves.

Just

a few yards beyond the site, we had an exhilarating view from the rim

of the Dry Creek watershed. Although we looked very hard, we could

not see Vultee Arch from the rim, finally deciding it was obscured

from our view by the west wall of Sterling Canyon. Later, I did

determine that it is 1.5 miles from the crash site at a bearing of

1630

true. The photograph below shows the rough, beautiful country spread

out below us.

|

Dry Creek watershed viewed from the Vultee crash site

|

On leaving the site, we

took the most direct route back to the junction of FR 231 with old FR

231. Meanwhile, three hikers had gone on ahead to retrieve vehicles

and meet us at the junction. We all then drove back to the parking

area to retrieve a vehicle still parked there. What had been

intended as a stroll in the woods, so to speak, become a good hike by

the time we had finished and we surely would not have found the site

at all without the help of Bill Reller and the information provided

by the tower attendant.

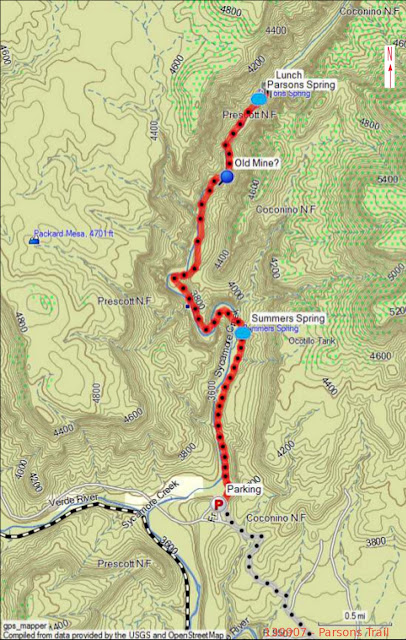

The

following map (below)

shows the immediate area of the crash site and the fire tower.

Forest Road 231 is shown in purple, the short drive from FR 231 to

the rim parking lot is shown in yellow, the dark green line shows our

hike to the tower and the red line shows the most direct route from

FR 231 to the crash site. The light green line is A B Young Trail.

It is 1.1 miles in length, so a 2.2 mile round trip hike will get you

from a car parked at the junction to the site and back. The next

time we will know this.

|

Close up map of the Vultee Crash Site and the East Pocket area

|

While we were rambling

around searching for the crash site, I found a few colorful flowers.

The most attractive of these is shown here (left).

I am not sure, but I think it may be a desert dahlia.

While we were rambling

around searching for the crash site, I found a few colorful flowers.

The most attractive of these is shown here (left).

I am not sure, but I think it may be a desert dahlia.

Meanwhile, Akemi had

become fixated on mushrooms. She photographed a number of different

specimens, sending those she found most interesting to me for

inclusion in the hike report.

Below are Akemi's

mushroom photographs. The colorful, spherical one (first two photos

below) is poisonous and psychoactive. It was featured in a recent

issue of Arizona Highway Magazine4

and erroneously listed as edible, causing that issue to be recalled.

|

Fly agaric or fly amanita mushroom

|

|

Fly agaric or fly amanita mushroom

|

Of the two photographs

below the one on the left was included because it is shaped like a

heart. The one on the right, on the other hand, turned out on closer

examination to be the author taking a nap.

|

Heart-shaped mushroom

|

|

The author posing as a mushroom

|

We actually hiked 5.4

miles. But just hiking from the FR 231/old FR 231 junction to the

crash and back would be 2.2 miles with an elevation gain of 210 feet

and a highest elevation of 7025 feet.

1

http://verdenews.com/main.asp?SectionID=74&SubsectionID=114&ArticleID=43609

2

http://verdenews.com/main.asp?SectionID=74&SubsectionID=114&ArticleID=43609

3

http://www.dmairfield.com/people/vultee_je/

4

http://arizonahighways.wordpress.com/2013/09/13/arizona-highways-magazine-issues-statement-about-october-issue/